|

I invented one of the coolest new products in my industry (gardening) in the last fifty years and I didn’t know how much to charge for it. I knew after all my years in business that the one thing that probably has the biggest effect on sales is pricing. And most people have no clue how to set a price which can be equal parts, psychology, research, analytics, and trial and error. An enterprising attorney I had met some time ago at the Licensing Expo in Las Vegas, set up a meeting with Vince Offer — the ShamWow pitchman legend who had become somewhat of a cult star with the millennials. He was interested in featuring my newly released product, the VeggiePOPS seed starters (now called SeedPops), on one of his infomercials. We met in nearby Santa Monica for coffee where he divulged that his name was really Offer Shlomi, and that he changed his name to Vince because he was a huge fan of Vinnie Barbarino, John Travolta’s character on the iconic 70’s television show, Welcome Back Kotter. “What a coincidence!” I said, “Because my ex is the late Robert Hegyes who played Juan Epstein in Welcome Back Kotter, and they were close friends.” John is the Godfather to Bobby’s daughter Cassie, who I raised as my own (and helped me develop the SeedPops). Vince was a fascinating guy who innately knew more about pricing than just about anyone I had met in my thirty years of business. Vince went on to explain that before he agreed to take on any particular product, he insisted that a booth be set up at the Rose Bowl Flea Market in Pasadena so he could see first-hand how well the product sold. I had previously been a cofounder/partner in two successful companies — toys and apparel — and we sold to mass merchants like Target and Walmart for the former and “high-end” department stores like Bloomingdales and even Barneys for the latter. The idea of selling at a flea market seemed beneath my pay grade, but I agreed to his terms with curiosity, and wow, (or Sham-Wow), I was glad that I did. I secured a booth at the flea market and roped Bobby’s son, Mack, who I also helped raise, into helping me transport, set up and man a pop-up tent, boxes of product, folding table, etc. and we embarked at sunrise for the Rose Bowl on a sweltering August morning, the second Sunday of the month. After setting up, we stood behind the table as buyers strolled by. I displayed the Pops on several lollipop stands — each holding forty eight. The whole presentation looked immensely colorful and appealing. Initially, when attendance was sparse, people would stop, marvel at the Pops, and buy one or two. We had priced them at $3.99 each. By lunchtime we had sold about half a single display — 24 pops. How did I come up with that price? I used Cost Plus pricing, defined more fully below. In addition, I researched packets of non-GMO, organic seeds and found that they ranged from about $2.00 to $4.99 depending on the vegetable, seed packager and store. My price point of $3.99 seemed reasonable. Around lunchtime, Vince Offer showed up, looked around the table, observed the people buying the Pops, and after awhile said, “This is what we’re going to do. You have six different colors, six different vegetables. You’re going to offer people (Offer, ha!), $20.00 to buy five and we’ll give you the sixth Pop for fee.” Within an hour, we had sold out. In terms of price, that amounted to $3.33 per Pop instead of $3.99. Price Setting Checklist Does the World Need Your Product? This is a tough question and not really within the scope of this article. There have been entire books written about it. I recommend reading, The Lean Startup, by Eric Ries. A good place to start by asking, “Is this a product that I want or need or could use that I can’t find in the marketplace?” To quote an old saying, “Can I build a better mousetrap?” Or, “Can I make the mousetrap more affordable? Prettier?” I recommend starting by observing your closest competition. Competitive Analysis If you are making a product that is not patented or otherwise protected, and other companies are making a similar product for $50, you are not going to be able to charge $100.00. So, keep that in mind. If you cannot do it for $50 without losing money, then you’re probably in the wrong business or you have to closely examine your costs and see where you can save money. Also, if you can somehow give the impression that your product is super special, build your brand awareness so that everyone wants your baby doll or cashmere sweater, then you can charge more. Building brand awareness is hard and expensive though. If you are making your shirt out of silk and your competitor is making it out of polyester, you can charge more for yours. If your workmanship is superior, you can charge more for that. And it depends where you’re selling it, too — online stores or brick and mortar. These are all considerations in setting a price. So start with a competitive analysis. List all your direct competitors and what they are charging. Make a note of how they have differentiated their products. For me, I knew that there are a lot of seed starters out there, but they are all the same, all brown and boring cups, and I felt like I could build a better mousetrap. Also, I had been working with schools putting in school gardens for several years. I noticed that there are three things that made a big difference:

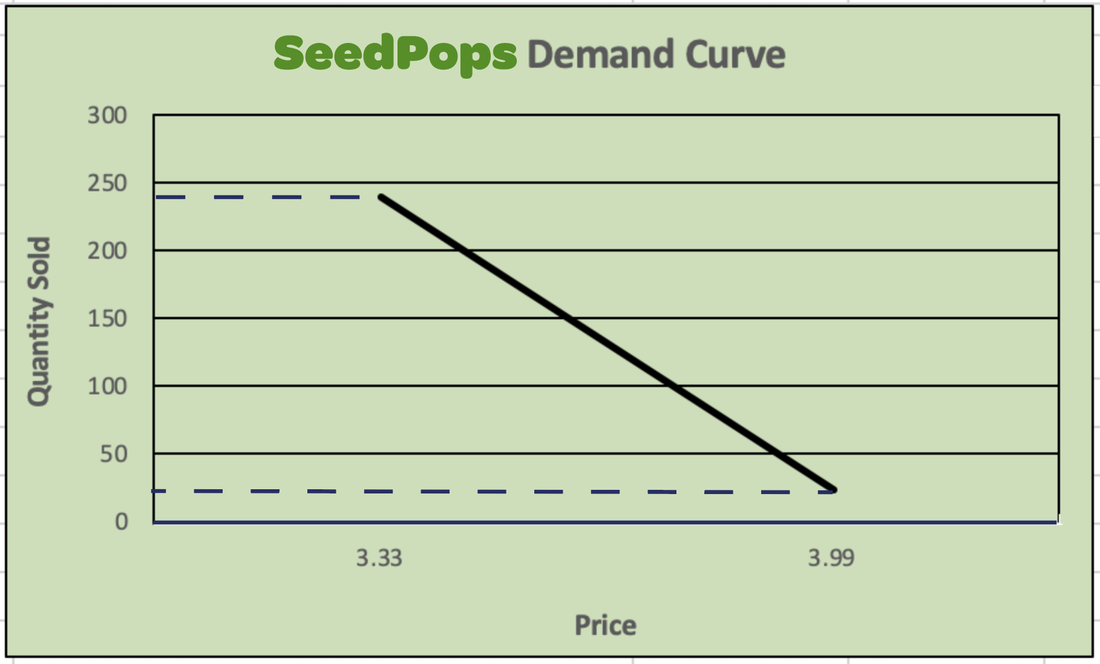

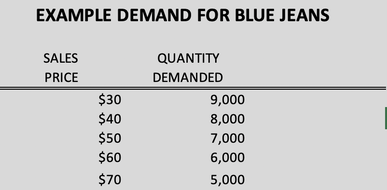

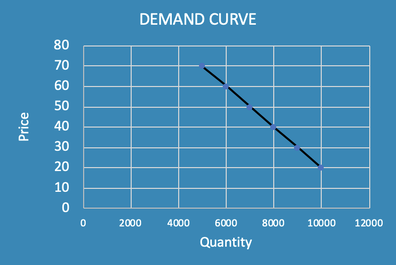

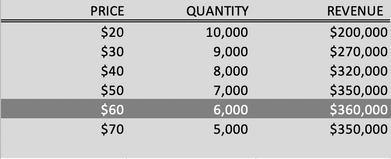

I knew I could build a better mousetrap and together with my daughter, Cassie, we set about building a better mousetrap — hence, the SeedPops were born or created as it were in our kitchen with newspaper, my food processor, some donut hole trays, paint, soil, fertilizer, seeds, and my oven. But what would we charge for them? A lot of pricing decisions come down to competition, but, there are also pricing models to consider and they all have their plusses and minuses. Choose a Pricing Model Pricing of course, depends on what you are doing, e.g. software, consumer products, business to business, services. There are a lot of different pricing models and you’re probably personally familiar with most of them. Believe it or not, one pricing model is “free”. You may recognize Facebook or Twitter as free pricing that later — when they had enough users –could charge for advertising. There is also: subscription, freemium, hourly rates (many service providers), project-based, value-based pricing, equity pricing, velocity pricing, and cost plus pricing to name some. You can look all of these up, but for the purposes of this article, I’m going to focus on cost plus because that is where most of my experience lies and that is the most common method for consumer products. And I’m going to focus on selling directly to the consumer such as an online store or in my case, the flea market. It is the easiest way to go into business because you are not dependent on selling to a store and you can easily try different prices. Cost Plus Pricing Defined I have a friend who is a new entrepreneur and recently started her own apparel company with a really cool product. I’m a hard sell and I love it. She is concerned that her online price matches her store price and are her prices too high? Are they too low? Is she making enough money to make her side hustle worth it? What should her sales channels be and how much should she charge for each of them? Should she put her products on sale? And when? I explained to her the idea of the cost plus pricing model and told her to start with that. Cost plus starts with a very accurate cost sheet including every tiny thing — every label, thread, tag, fabric, pattern, cutting, sewing, and so on. After adding all of your costs, double them — and that becomes your wholesale price. If you sell to a brick and mortar store, they would typically double it again for the end consumer. Understand that doubling the price is a 100% markup. The Importance of Accurate and Complete Cost Sheets What you don’t want to do is make a careless mistake on calculating your costs that will affect your sales price. I’ve seen that happen. You cost your sewing at $5.00 an item when it’s really going to be $15.00. How do you determine your costs? Get firm quotes in writing from all your subcontractors and suppliers. When I say you have to include every teeny tiny item, I mean it. Not just printing your hang tag, but the cost of the safety pin that attaches the tag. The plastic bag that you place your item in. Everything little thing. Make a spreadsheet or list it out on a piece of paper, it doesn’t matter what method you use. Just make sure you are accurate. This is vital because you don’t want to price your product below your cost. Sounds obvious, but if your costs are inaccurate, how do you really know? Minimum Order Quantities or MOQs If you are buying component parts from another manufacturer and most likely you will be, make sure you find out if there are minimums (MOQs) that you have to buy. Example: You are in the apparel business. You are going to print your fabulous graphic designs on camouflage t-shirts and sell them. You think you can sell 500 shirts to your friends. You go to your t-shirt manufacturer and put in an order for 500 camouflage t-shirts. She says, sorry, our minimum is 1,000. Don’t do it. Haggle with her. Or, find a manufacturer who will sell you 500, even if you have to pay a premium. A very wise person (my accountant) taught me a saying for manufacturing or assembly: First Loss is Best Loss. In other words, better to write-off fabric at $10.00 a yard than completed garments which use that fabric, plus sewing cost, thread, labels, etc. Fabric is a smaller loss than a finished garment. The most common reason why companies go out of business is because they make too many products (inventory) and all their money is tied up in those products that they can’t sell. Because we are using a cost plus pricing model, the direct to consumer sales price has to be at least double your cost — more if you plan on selling to brick and mortar stores later because they will have to take their 100% markup. For my example, because I was selling directly to the consumer, e.g. the Rose Bowl Flea Market, or if you selling through your own online store, you have the ability to do an A B Testing of sorts. You can change your price and see how that affects your sales! That was the genius of Vince Offer. Construct Your Own Demand Curve A typical Demand Curve is negative. This is just common sense. The more you charge, the less you sell; price and quantity have an inverse relationship. This is a microeconomic concept and like anything in economics, it’s sometimes more of an art than a science. Why? Because other things may come into play — like the time of day or the weather or one location is better than another. That’s why it’s good to try to hold all other things equal. This is obviously difficult if you are selling to brick and mortar retail stores because you sell to them in bulk and they set their own price. You can’t sell them two sweaters at $20.00 and 5 at $30.00. But if you are selling online directly to the end consumer, you can easily change the prices. That’s why I recommend you launch your product first by selling directly to the consumer. Here is the very simple Demand Curve from that day at the flea market. Pricing Psychology You can see that when I charged $3.99, I only sold 24. But on the same day, with the same product, in the same place, when I lowered the price to $3.33, I sold 240. I didn’t sell it like that though — putting the price tag at $3.33 — I sold it in a different way: buy five get the sixth one for free. That is where the psychology comes in. People liked that they were getting all the different colors and all the different vegetables and they felt like they were getting it for a deal. Which they were. Another way that psychology comes into play is when will buy more if the price is higher. This is called a Luxury Demand Curve — people think they are getting a more valuable item if the price is higher so they buy more. What Price Generates the Highest Sales? After you test your different price levels, you should then figure out which price generates the highest sales volume. Your total sales or gross sales are just the quantity sold multiplied by the price. In my SeedPops example, clearly, my total sales were much higher at $3.33 vs. $3.99: $799.20 vs. $95.76 respectively.  But let’s say you are selling blue jeans and the sales numbers were closer at the different prices. Your customer’s demand might look like this chart to the left.  And your Demand Curve would look like this chart. At $30.00 you are going to sell 9,000 pieces and so on. But what price will give you the optimum sales (also called revenue)?  Let’s calculate what your sales are at these different prices. Here we see that the highest revenue made is from pricing the jeans at $60.00. Emotional Considerations

Almost worse than inaccurate costing or building too much inventory is to lowball your price because maybe you have an inferiority complex or you don’t think your products are worth it or you don’t think you are worthy or deserving. You’d be surprised how often this happens (including with yours truly). Remember these four rules:

If Vince had told me to sell my SeedPops at $1.50, I wouldn’t have done it. Recap on Pricing

Final Note: you don’t have to make excuses for your pricing and I don’t think you really have to apologize for early adopters that your prices are now lower. Think about the first customers for the calculator. They paid hundreds of dollars for something that we get for free on our phones. Hewlett Packard is not worrying over the fact that early customers paid $200.00 for one of their calculators. And what happened to me and my SeedPops? I decided not to do an infomercial with Vince — I went the way of getting a licensee to license my invention. They do the manufacturing and sales and pay me a royalty. My SeedPops are now found in thousands of stores all across North America including Target. On a side note, my attorney also asked a friend of hers to meet me at the flea market that day because he was a consultant that helps companies expand overseas. I am currently in talks with a Dutch company to sell SeedPops in Europe, and a company for Australian distribution. That consultant and me? We are now a couple. Happy ending. I’d love to hear your experience with pricing and any questions you might have.

1 Comment

I am a founding member of an active startup founders group. We started with a dozen or so entrepreneurs and I appreciated it because being a startup founder without a partner can be a lonely endeavor. I’ve seen a lot of fellow entrepreneurs walk in and out of the doors over many years. I can now tell if someone is going to “make it” after about three meetings. Here are my observations of why they eventually don’t succeed: 1. They don’t show up. If you want to be successful, you have to show up. I mean that literally and figuratively. You have to show up on a consistent and regular basis. Even if you are tired and can’t seem to find your customers, you are not booking sales, you are getting rejected and you know deep inside your gut that you probably have to pivot your plan, even though you are exhausted. You must keep going — putting one foot in front of the other, executing the marketing plan, calling on customers, pivoting if necessary — you just keep at it. Do they show up on time? If you can’t show up at our meetings on time, what about their business meetings? What if you have a meeting with a venture capitalist? Are you going to be late? Are you going to flake and not show up? Because you and your husband had a fight? Being a C.E.O. of your own startup company is being a self-starter in the truest sense. If you aren’t 100% committed to this, you just won’t make it. 2. They aren’t willing to sacrifice. There is a lot of inherent sacrifice in starting a company. Generally, you have to work long hours, drain your savings, if you’re lucky enough to have some, borrow from friends and family to get started, if you’re lucky enough to have some, give up the money you would make in another job which is called “opportunity cost” and give up time with your family and loved ones. Whenever I see that members aren’t willing to make sacrifices, I know that they are finished. And it has happened with regularity. Usually they will take a job and not come back. Prepare yourself for a lot of sacrifice and if you’re not willing to accept that, you won’t make it. 3. They don’t accept the fact that it’s most likely going to take a long time. This is closely related to sacrifice, but it’s more than that. There is a perseverance factor to it and a necessity of faith. A major problem that I’ve noticed is what I call, “The Spouse Factor.” It’s when the spouses, usually women because most founders are men, I’m sorry to say, think it’s taking too long and give up on their husband’s dream. It is sometimes accompanied by ultimatums and all kinds of bad behavior that I won’t go into here. And it’s sad, really. Because you have this person who is putting it on the line every day working as hard as they can. They are trying to have faith in themselves. Some spouses won’t even get a job. Sometimes the lack of support is breathtaking. My advice is to talk to your spouse before you start a company and make sure they are completely on board. For a long time. And make sure you are, too. The myth of starting a company and selling it to Facebook in three years is just that. It’s a myth. If you don’t know this going into it, you won’t make it. 4. They can’t, or won’t sell what they are making. My first job out of college (Penn State) was selling encyclopedias. I generated my own warm leads by doing magic shows at pre-schools and elementary schools. Yes, I became sort of a magician, and I was good. My low point in the job of selling encyclopedias was going into apartments, in the Housing Projects in Washington D.C., where the rats were as big as possums and the cockroaches ran along the kitchen walls with impunity like it was the Capital Beltway - at a time when my potential customers and I were sitting there talking with the lights on! That year, in between undergrad and grad school, I made over $40,000.00 (almost $119,000.00 in today’s dollars) and I was able to start paying for my first year of grad school at Georgetown University. Moreover, I learned how to sell. Steve Blank, the famed Silicon Valley entrepreneur and Stanford University professor says, “you will find no answers inside your office”. You have to “get out of the building and knock on doors”. I believe that is something very few people are comfortable with, but one that every entrepreneur must learn. I don’t care what you end up doing in life, and I don’t care how you do it, but learn to sell. If you don’t, you won’t make it. 5. They don’t take advice. In our group, members present the most pressing issue that they are dealing with that month, and we have a methodology to “process” that issue. It includes a lot of questions and a lot of feedback. When someone is taking the time to give you advice, especially if it is in a group and collective intelligence is at work, you should listen. Try not to be defensive. And you should take action on that advice. After every processing session, that person is given a Call to Action, or CTA. If they come back without seeing their CTA through, that does not bode well for them. As a startup founder, you are going to need advice from other people because there is no way you can know everything you need to know to do this. I’m not saying you have to listen to everything everyone tells you, but I am saying that if you have smart advisors, or paid professionals, you need to be able to evaluate their advice and act on it. If you can’t, you won’t make it. 6. They aren’t willing to change. Are they so entrenched in their vision that they can’t accept that the world doesn’t want their exact product or service, or that there is something wrong with their product, service, or business model and it needs to be changed? Almost every startup business has to pivot. What is a pivot? It’s when you change your business model in some way because your current model isn’t working. In my latest business, Bloomers Island, I’ve pivoted four times. I know it can be exhausting after your first try and it’s difficult to start over. If that’s the case, take a couple weeks off. I got so burned out after my first couple of years and first couple of pivots, that I went to South America for six months. It was the best thing I ever did. At the end of the day, if you’re not willing to make changes, you won’t make it. 7. They aren’t comfortable crunching numbers. I have seen many people start a business without knowing how to construct a basic income statement let alone a balance sheet. They try to make decisions based on imperfect information. In our group meeting, if a member is presenting an issue to the rest of us, looking for us to help them decide between two alternatives, I always ask: “What are the numbers?” I’m not saying you have to be a CPA, but it wouldn’t hurt to take a basic financial course, or sit down with a friend who knows numbers and cook them a dinner to show you how to construct a set of financial projections. If you look at the numbers — the cost of doing one thing with a projected outcome versus the cost of doing another with that projected outcome (otherwise known as a Cost Benefit Analysis), the answer usually becomes clear: crystal clear. The truth is in the numbers. Get comfortable with numbers or you won’t make it. 8. They are overly emotional. My favorite line in the motion picture “The Godfather” is when Sonny, Michael and Tom are talking about killing the bad cop. That is when Michael says, “It’s not personal, Sonny, it’s strictly business.” Of course, Sonny was made vulnerable because he was too emotional. His enemies knew that and they were able to kill him. Don’t be overly emotional. In A League of Their Own, Tom Hanks’ character says, “There’s no crying in baseball!” Well, that applies to business, too. You’re going to get rejected and criticized and insulted. Save your crying for the shower. Take solace in the fact that the more you are rejected, the easier it gets. Develop a tough skin. If you don’t, you just won’t make it. What is an honest appraisal of my weaknesses? Number three and number six. I was unrealistic about how long it would take. I was too invested in what I wanted to do and took too long and wasted too much time and money before pivoting. I kept going though, because I do the other things really well. Now, it is finally paying off. Several years ago, during a family vacation to North Carolina, a small contingent of us visited The Wright Brothers Museum at Kitty Hawk. Etched around the base of the memorial on the hill where the first flight was made were the immutable words, “In commemoration of the conquest of the air by the brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright. Conceived by genius. Achieved by dauntless resolution and unconquerable faith.” Numbers 1 through 8 on my list? Check, check and check.

In closing, “Ladies and Gentleman, start up your engines and good luck.” It was the 1980s, a time of Talking Heads, padded shoulders and big hair. I had just graduated from college with a B.S. in Agriculture. A younger sorority sister of mine at Penn State with a really cool name, Mimi Roma, told me she was moving to Washington D.C. with her boyfriend and was going to finish her degree at Georgetown University. I didn’t know of Georgetown. I was a country bumpkin from Western Pennsylvania who only applied to one college and didn’t even know the meaning of Ivy League. I also didn’t know exactly what I was going to do after college. I didn’t have anything lined up. The United States was in the middle of a terrible recession. I went to the library near the grassy center of campus and looked up Georgetown and saw that it was considered one of the best universities. I didn’t know anyone in Washington D.C., but I got the idea that I should go there, too. My boyfriend agreed to move there with me. He had some fraternity brothers who were renting a house in nearby Alexandria, Virginia, and they could rent us a room. We drove there in my bright orange Ford Pinto with one hundred dollars and a couple of suitcases. We clutched on to the concept that with our degrees, along with a hope that only a freshly educated co-ed can realistically muster, we could find jobs. Things were rough. The two of us slept on a single bed. My first task was scrubbing the bathroom we shared with four other guys. Boys can be so filthy. That first year, I hawked encyclopedias door-to-door. That was one of the best jobs I’ve ever had in terms of learning to sell and overcoming rejection. It was an education in and of itself. My boyfriend couldn’t find a job. Finally he found one, but it wasn’t in the Washington D.C. area and so he moved away. I stayed. Back to my idea to attend Georgetown University. I took my GRE. Got my undergrad transcripts and the whole nine yards. Referrals from three of my professors. Applied. Started taking part-time night classes in the interim. Met and pretty much camped out on the doorstep of the Chairman of the Economics Department. Finally after doing well the first semester, I was accepted and given a fellowship. Execution. Washington, D.C. was a wonder. Although it is small compared to cities like New York, Chicago and Los Angeles, to me it was vast. I was nervous just driving around the Beltway. I walked everywhere I could with my worn tennis shoes and Sony Walkman. I passed iconic government buildings on the mall, like the museums and different Cabinet Departments. There was also The World Bank and the Peace Corps. I had the idea, I can work at one of those places. And I did. I became a typist for the CIA. I got an internship at HUD where I wrote a book that was published. I made a friend in my graduate program and he introduced me to my future boss at the World Bank. Execution, execution, execution. Looking back, my entire life has been about coming up with ideas and executing them, by almost any means necessary. And it has been that way with my business today, Bloomers Island. I nurtured the idea for a long time, then raised seven figures and started executing. I won’t go into the nitty gritty of it and how difficult it has been the last few years (my investors have been both patient and supportive), but I am starting to see a light at the end of the tunnel. To be sure, it is a light that at any moment can be snuffed out, but it is there, faint, dispersed and faintly glowing through the fog of the future. It was one of my most trusted advisors who first uttered the saying to me, There is no such thing as a good idea, there is only good execution. Immediately it was love at first hearing. How many times has someone told me that they have a great idea, this or that, and I listen to them and know they will never execute; they will never put in the work and dedication, along with the money and the risk, to bring it to life? How do we bring our ideas to life? How do we bridge the gap between coming up with brilliant ideas and then following through on them? I did some research on this, and thought a lot about how I have been able to bring my ideas to life. This is what I do:

1. I honor my ideas. I write them down. I try to bring them to life. 2. I tell everyone I know. You never know who is going to share your enthusiasm. It might even be a potential investor. 3. I figure out a way, strategically and tactically to achieve my ideas. I make a plan. 4. Failure is never an option for me. I burn my ships. 5. I am patient, but not so entrenched that I am not willing to pivot. 6. I persevere. Character is sticking with a project long after the mood has passed. I forget who said that, but it’s true. Perseverance is about 90% of success. Think about all the times you came up with an idea and then executed it. You can repeat that! It doesn’t matter if you work for yourself or work for a large company. Let me know the best idea you ever had that you were able to execute. Here are some great articles that may also help if you’re struggling with bringing your ideas to life. My last article on Medium : Where The Heck Is My Comfort Zone And How Do I Get Out Of It? The 12 Things That Successfully Convert a Great Idea Into a Reality by Glen Liopis for Forbes. How to Execute Great Ideas by Marla Tabaka for Inc. How Do I Actually Execute On My Ideas by Art Markman for Fast Company. Eventually, Mimi Roma and I drifted apart. The funny thing is, she never went to Georgetown. But I did. |

Stories and snippets of wisdom from Cynthia Wylie and Dennis Kamoen. Your comments are appreciated.

Archives

June 2024

Categories |