|

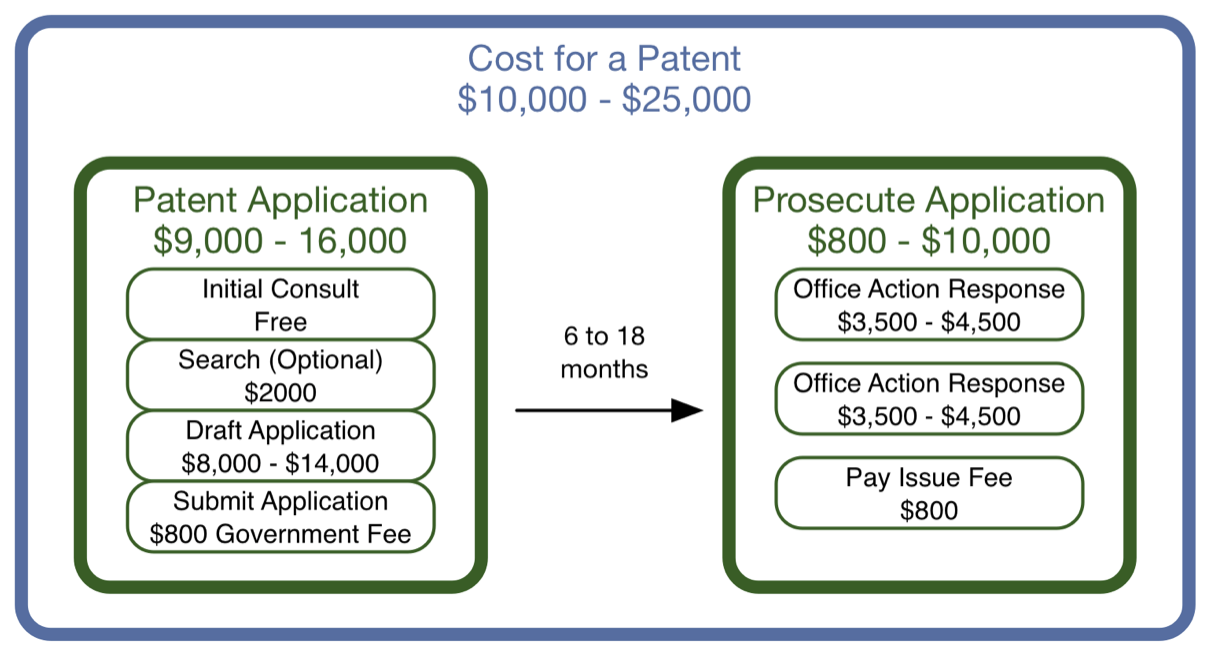

One of our clients has an incredibly valuable series of patents. The highly effective product made by his patented manufacturing system has recently skyrocketed with the pandemic. His timing was excellent by any estimation. The only problem is that several companies have blatantly knocked off his product without any repercussions at all. Why? Because he doesn’t have the enormous resources necessary to sue those companies for patent infringement. But let’s back up a moment. The Ridiculous Cost of a Patent According to Bitlaw Guidance, a patent attorney will usually charge between $8,000 and $10,000 for a patent application, and the cost can be higher. In most cases, you should budget between $15,000 and $20,000 to complete the patenting process for your invention. They’ve constructed a great graphic to show the costs by tasks. (This does not include international patents which are also very expensive.) If you wonder if you can go ahead and use your patent (sometimes referred to as the poor man’s patent) to make and distribute your product before you patent it, in most cases it will not hold up in a court of law.

What About Litigation? Let’s say you spent $20,000 and got your patents and someone violated it. You then have to be in a position to sue them to stop using it. Patent litigation costs between $2.3 million and $4 million on average, and it takes one to three years for a patent case to reach trial. Patent infringement lawsuits are settled in 95 percent to 97 percent of cases. In conclusion, I’m not saying, don’t get your patent. I’m just saying, make sure you have the money set aside to do so and also to fight any infringers. Otherwise, skip the patent, try to be first to market, and establish your customer base based on other tangible benefits like customer service. Disclaimer: I am not a patent attorney, I am just a patent holder. So check with your lawyer to confirm anything I write about here. Subscribe to newsletter on LinkedIn.

0 Comments

Best Use: Increase the accuracy of any forecast.

In 1906, Francis Galton discovered what we now call, the wisdom of crowds. At a farmers’ fair in Plymouth he came upon a contest where crowd members had to guess the weight of an ox. Around 800 people wrote their guesses on tickets and the person with a guess that came the closest to the actual weight won a prize. The interesting part of this contest was the analysis Galton did afterward. He added up all the weights guessed and took an average. It turned out that the average was remarkably close,It turned out that the average was remarkably close, much closer than the winner, and even closer than some of the experts in the crowd. The average was only one pound off. This experiment has been repeated many times over the last century. One talked about is the Jelly Bean Experiment. A finance professor, Jack Treynor ran this experiment with his class of fifty six students. He filled a jar with 850 jelly beans and had his students guess. The average estimate was 871 — a difference of only 2.5%. Only one person in the class made a closer guess. In 2004, James Surowiecki drilled down into this phenomena with his acclaimed book, The Wisdom of Crowds (Doubleday). In his research he discovered important information about the crowds. Not all crowds are wise. As an example, investors in a stock market bubble. According to Surowiecki, for the wisdom of the crowd averages to work in their intended way, the information collected had to meet five criteria[1]: 1. Diversity of opinion — Each person should have private information 2. Independence — People’s opinions are not determined by the opinions of others participating. 3. Decentralization — People are able to specialize and draw on local knowledge. 4. Aggregation — Some mechanism exists for turning private judgements into a collective decision. 5. Trust — Each person trusts the collective group to be fair. The book received rave reviews. BusinessWeek wrote, “Provocative …. Musters ample proof that the payoff from heeding collective intelligence is greater than many of us imagine.” Applying The Wisdom of Crowds to Your Business A terrific August 2022 article in Harvard Business Review by Don A. Moore and Max H. Bazerman, “Leading with Confidence in Uncertain Times,” advocated using the concept of wisdom of crowds in forecasting. The question posed was if companies should rely on one expert forecast or many forecasts averaged. They posited that the higher risk of companies is to depend too much on one expert economic forecast. They reported that, averaging the estimates of all of the economists in the survey is a better strategy than selecting the estimate of the best predictor from the previous year. So how can you, as an executive, take advantage of this concept? Gather the opinions of as many knowledgeable stakeholders as you can. This can be done creatively with different “crowds.” 1. Ask your employees. Who knows your company better? Make it anonymous to get more authentic answers. 2. Ask your customers. When is the last time that you sent out a survey or email where you asked your customers about your products or ways for you to improve? I don’t know about you, but I’m sick of getting a survey every time I buy something. So come up with a creative way to get people to respond. Try telling a story. Use the story I told about the ox and the fair and the wisdom of the crowd. I would respond to that. 3. Ask your vendors. I always say that a company is only as good as its vendors. You buy things from them, so the least they could do is spend a few minutes answering some questions. Besides, it may benefit them. If your business increases because you are making better business decisions, then conceivably you would buy more products or component parts from them. 4. Ask the internet. Social media. Followers. Fans. You can definitely reach more people through the internet. This is appropriately your largest audience, your largest crowd. The idea here is to get your dedicated fans to respond. If you don’t have dedicated fans, then you might have bigger problems. 5. Ask your shareholders or investors. Of course you would have to tailor the questions you ask to the audience you reach out to. I wouldn’t talk to your vendors or customers necessarily about your projected revenues or profit numbers. Using the Results There are plenty of questions you could ask your crowd. This method works best as a prediction or projection of unknown numbers. So you need to put choices in terms of numbers. As an example, let’s say you ask your ten-person sales department what they think sales will be next year. Write down all the estimates and then take an average. Using the average sales number, you could ask your shipping department of twenty employees, what they think total dimensional weight cost for freight will be for the upcoming year. You can ask qualitative questions and attach numbers to the answers so you can get an average. You could post an ad campaign on your social media and ask your followers to rate it from one star to ten stars. Then take an average and if that is a 10, then run that campaign. If they rate it as a one or two, you’d better start to work on another campaign. As Moore and Bazerman so aptly pointed out: “It is our craving for certainty that leads us to chase a single expert, the one who can make perfect predictions. And this craving also makes us vulnerable to charlatans who lie to us and pretend they know; or worse yet, those megalomaniacs so overconfident that they sincerely believe they know. Beware the leader, entrepreneur, or political candidate who claims certainty about an uncertain future. They reveal more arrogance than insight.” [1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Wisdom_of_Crowds Subscribe to my LinkedIn newsletter. Originally published at https://www.datadriveninvestor.com on April 20, 2023. Lately, I've been watching a lot of detective shows on television. If there is a murder (and there's always a murder), the detective's job is to collect every bit of information that they can. They observe the murder scene. They take photos. They take fingerprints. They interview all the relevant people in the victim's life. They pull documents on the victim. Were they ever convicted of a crime? And so on. The same kind of deep dive information collection can be the single most powerful tool to change anything in our life and in our business as well. Want to get your finances into shape? Measure everything you spend your money on. Want to lose 10 pounds? Measure everything you eat and how much exercise you get. And here's the really cool thing: simply by virtue of the fact that you are collecting and measuring things, you can change their outcome. I wrote about this recently in my article about the Observer Effect. Sometimes, it can be tricky to collect data for your business. Here is a great chart from Research Gate to fine-tune your information collecting methods. When running your business think of yourself as a detective. Collect all the information that is possible. A much clearer picture will eventually evolve. If detectives can find a murderer, you can find the bottleneck in your operations, the most effective marketing campaign, or the highest profit products. Then use that information to take your business to the next level. Subscribe to my newsletter on LinkedIn. |

Stories and snippets of wisdom from Cynthia Wylie and Dennis Kamoen. Your comments are appreciated.

Archives

June 2024

Categories |