|

He was running out of time. Our client’s warehouse was in a rustbelt town, he needed to sell it and no one was rushing to buy it. The weeds were growing through the cracks in the parking lot and he couldn’t cover the mortgage payment with his cash flow for much longer. This client was a perfect candidate for the 21 Reasons exercise.

In our Startup Founders group, we would task a participant to write down 21 Reasons in regards to anything they were struggling with. This came from our leader, John Morris, who is brilliant about startups, raising money and other esoteric businessy things. It probably came from someone or somewhere else, like most great ideas, but after many Google searches I couldn’t find anything. So, I’m giving John the full credit. The Methodology Write a list of 21 Reasons why someone would want to do whatever it is that you want them to do. One of The Project Consultant clients needed to sell a warehouse, and sell it quickly. It had been on the market for almost two years. He was willing to lease it as well, but he had already tried that to no avail. His broker brought in interested companies now and then, but not many and no one bit. My partner, Dennis, is pretty well connected in the real estate business; his dad was the top commercial real estate company in Connecticut before they sold it to Grubb & Ellis. And I was a partner in my own real estate investment company in Southern California for many years. Despite our knowledge and contacts in the real estate business, the first thing we did was ask our client to list twenty one reasons why someone would want to buy his building. And we promised him that if he did, his building would sell. What? The First Six You might ask the value in doing this exercise. Fair question. As John Morris explained, the first six reasons are usually easy. They are the obvious things. The building is 100,000 sq. ft. which gives you room to grow. There is a rail spur behind the loading dock. Speaking of loading docks, we have ten of them. We just replaced the roof five years ago. The parking lot can hold a hundred cars. The Next Ten The next ten reasons are a little more difficult. You have to think about the less obvious things, like we’re including industrial shelves with the building. There are ten offices, too. The view from the main office looks out onto the river. There is a great security system built-in. It’s only five miles to the nearest interstate freeway and so on. The Last Five Then you get to the last five. You’re going through this process and you come to the last five reasons and you have to dig deep. Deep. There’s a fantastic deli within walking distance. Or, the offices are painted in a soothing shade of blue. I don’t know. It’s your building. What do you like about it? You can live on a farm on rolling hills nearby where the fog settles among the treetops every night. Your husband can buy a horse. The local town has an October Fest that can’t be beat. The Psychology Behind This By listing all these things, you will shift your mindset. That makes a difference in whatever you’re trying to achieve. Not to get all woo-woo about it, but it’s kind of like manifesting. You attract a buyer to you because you are putting out into the universe thoughts and messaging about this amazing building that anyone should want to buy as long as they have a need for a warehouse. It also gives you more confidence when someone comes to look at it. You think, this is a fantastic building. I just listed twenty reasons why it’s a fantastic building. I’ll let you buy it if you’re lucky. Then, because my partner and I have real estate contacts, we convinced him to fire his agent. Dennis referred him to an international commercial broker he knew. The new agent had an enormous database of buyers from all around the world. That’s helpful because they might have known a company in Europe that wanted to open a satellite warehouse in the United States. And perhaps they never would have considered this particular area. In short, it increased the population of potential buyers. The building was sold in a month. It was purchased by a company that looked at it the year prior. That’s fine. Competition had become more intense with the new broker. And I’m sure that company was aware of it. There was now pressure for them to buy. They didn’t need that much space, but they took a chance and had a belief that their business would grow, and therefore, they would grow into the space. But in my opinion, it was the list. To be sure, the list did help them write a more thorough and attractive listing. But it was the power of our client believing in the value of his building. Some other lists we’ve worked on: 21 Reasons why someone would want to buy your medical practice. 21 Reasons why you should hire an assistant. 21 Reasons why you should buy out your minority partner. 21 Reasons why someone would want to license your brand. 21 Reasons why you should manufacture overseas. 21 Reasons why someone would invest in your startup. 21 Reasons why my nephew’s crush would want to go to the dance with him. Try it yourself. Consider a vexing problem you have. Write your list of 21 Reasons. Remember, it must be twenty one. Cynthia Wylie started her career in investment banking and left to start her first company. She has started/run/sold six companies. Through her last company, The Project Consultant, she has worked with many clients who were starting their own companies and/or launching projects in industries such as agriculture, publishing, toys, and apparel. She has extensive experience in consumer products manufacturing and importing as well as real estate investment. Her areas of strength include operations and finance, in particular, cash flow management and raising money. As a founding member of the L.A.–based entrepreneurial group, The Startup Founders, and a participant in Startup Chile, she has evaluated and assisted hundreds of startups locally and globally. She has a B.S. in agriculture from the Pennsylvania State University and a M.A. in economics from Georgetown University which she attended on a full fellowship. While a student, Ms. Wylie taught undergraduate courses in statistics and economics. She has also written five children’s books for an imprint of Penguin Random House and is a regular contributor about business and economics for the publication, Data Driven Investor. Favorite quote: The truth is in the numbers. Originally published at https://www.datadriveninvestor.com on March 2, 2023.

0 Comments

What are the biggest challenges you are facing in your business right now? I just posted this question on a small business group that I’m a member of on Alignable.com.

As a partner in a consulting firm, we are putting together updated, post pandemic marketing materials and fine tuning our message. I wanted to get an idea of the biggest problems companies are currently facing. Our economy has been through a lot the past few years. The responses I received were wide ranging and touched upon just about every area of business (with some surprises): delegating, ADHD, growing the business, raising capital, finding employees, raising prices, staying motivated, prioritizing, and closing sales to name several. I thanked all of those who replied and contributed some tidbits of advice. I couldn’t help myself. As a consultant, that’s what I do. One particular response was a business having difficulty getting his salespeople to close at a rate above 10–15%. I replied that he should check his industry’s standard closing rate because maybe 10–15% was within the norm. Many a company I’ve consulted would be thrilled with a 15% closing rate. (The average sales success rate across all industries is 3%.) I also suggested some sales training, because while research has been mixed on the effectiveness of sales training, some studies suggest it can improve ROI considerably. Lastly, I suggested his sales staff read the book, “The Asking Formula,” by John Baker. It really is a wonderful little book for sales and I recommend that everyone read it regardless of what they’re doing. He rather sanctimoniously said that he already has three sales trainers that he feels are the best in the world. One of them made $33 million in commissions in 10 years. And that, someone will not rise to his level reading from a book. Okay, but, what? Obvious first question, Why not use that guy for your sales instead of as a trainer? Maybe he’s retired? So, Why is your sales staff still struggling with the $33 million guy training them? Along with the gold, there’s a lot of questions in “them thar hills.” A Method to Find out What Your Problem Really Is It brought to mind the Startup Founders Group I was a founding member of many years ago. We met once a month to process issues. We started with a dozen or so entrepreneurs and I appreciated it because being a Startup Founder without a partner can be a lonely endeavor. We had a formal approach for processing our issues: Begin with a problem and put it into a question. It should take the form of How Do I (HDI). It can be business or personal, because if you’re having personal problems, it can definitely interfere with your business. After the issue was presented, there was a period of questions which the founder would answer. After that the other members would suggest a different HDI. We found that the problem members thought they were having, wasn’t really the problem. Almost always! Here are some hypothetical HDIs to give you an idea of the concept. 1. HDI increase my runway by raising money in a hurry? Could actually be, HDI cut expenses to decrease my monthly burn rate? 2. HDI deal with my partner who is an alcoholic and passing out in the middle of the day? Could be, HDI buy out my partner? (Ask him when he’s on a bender with pen and contract in hand. Just kidding.) 3. HDI reduce my dependency on one large customer? Try, HDI divert resources and update my marketing plan to attract new, smaller customers? 4. HDI get my spouse to be more supportive of my startup? HDI improve my communication skills so that my spouse understands the startup world. After the HDI is restated and accepted by the processing member of the group, (and they can choose between many suggested HDIs, or even their original HDI), we would enter the period of suggestions. These are ideas of how the member can fix their problem. During this period they need to remain silent and listen. We assign another member to take notes, so the issue processor can just listen. Upon finishing, the member taking notes will email those to the processor and then, the most important part, they make a promise or commitment to action (CTA). Relevant Questions to Ask Back to the sales guy on Alignable.com. The following are the types of questions he should ask himself after the first two obvious questions I mentioned earlier. Keep in mind some of the questions here included what are called, veiled suggestions. When you are processing, just ask questions. But for this article, I’ll include some suggestions along with the questions. 1. Again, what is the industry average closing rate? You didn’t answer that. 2. The $33 million guy might be a great closer, but a lousy teacher. That’s possible. Can he teach others? Perhaps he doesn’t like the task of training others? 3. Are the sales people you’re hiring any good at sales? Start keeping track of your sales data; who is the most successful and what are their methods? 4. If your sales people are underperforming, is there a problem with your product? 5. Ask top level interviewees that are declining to take a sales job with you, why? Maybe you need to offer a higher salary, commission rate or benefits. 6. In addition to training people to sell, are you training them about your products, all the benefits? 7. If appropriate, do you have a good prepared pitch? If not, maybe you need one. If so, maybe it needs to be better. 8. Are you providing your sales staff with good quality, warm leads? If not, maybe you could do that. 9. Is your product a commodity, based simply on price? If so, maybe you need to adjust your pricing. 10. If your product is not a commodity, have you developed reasons why customers should buy from you? Have you distinguished your company through customer service, or some other benefits? 11. Do you have a detailed marketing program to support your sales people? Do you have a marketing strategy at all? I could go on. But after all these questions are answered I think a new HDI suggestion would be along the lines of: How do I help my sales staff to be more successful? Then move on to the suggestions phase, many of which will be self-evident. That is the value of questioning whatever you think your problem is. You can use this process yourself, with your own company, for any issues you are facing. Better yet, get your employees to join in. They might know more than you. They’re on the front lines, after all. Originally published at https://www.datadriveninvestor.com on February 24, 2023. Subscribe to DDIntel Here. Visit our website here: https://www.datadriveninvestor.com And help their customers along with their own bottom line. It is always a win-win for financial institutions to reduce loan delinquencies. This has become especially important during the post-pandemic world with a slumping housing market, high inflation, raising interest rates and high levels of consumer debt. During the economic shocks of the last few years, however, we saw an interesting trend in delinquencies.

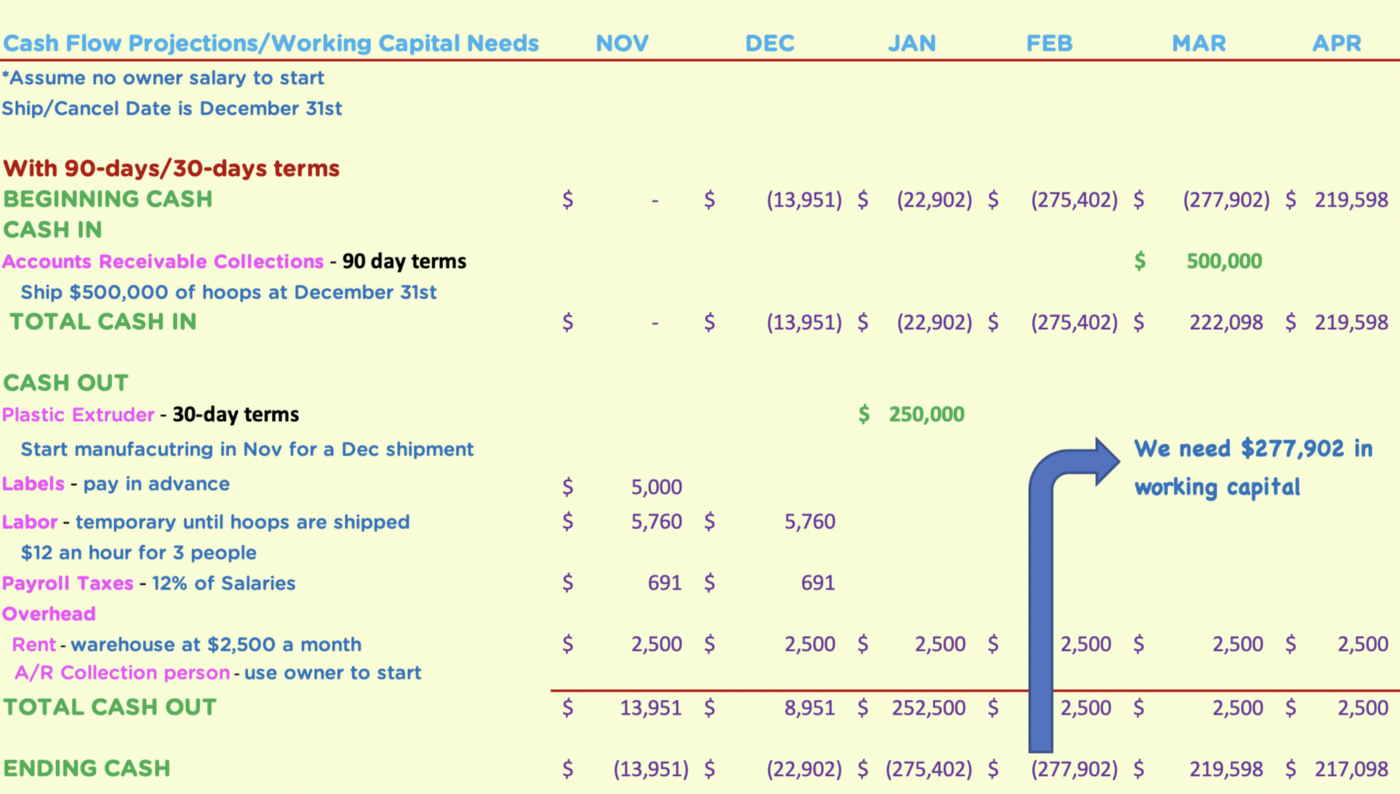

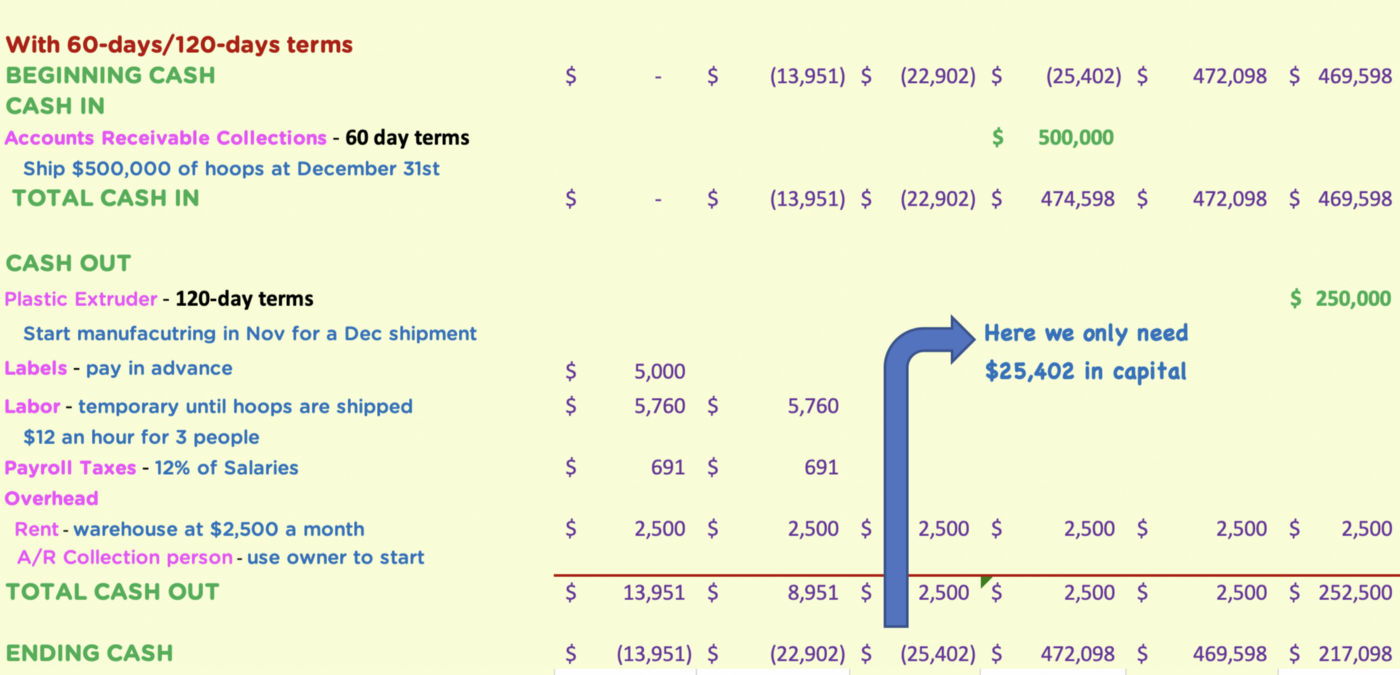

Spanish philosopher George Santayana is credited with the aphorism, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” As we navigate our current economic challenges, looking back at our most recent economic downturn, the Great Recession in the late 2000s, might provide some helpful lessons. In early 2009, I attended an economic forum with guest speakers from the banking, real estate, stock brokerage, and economic industries. At that time, there were many real estate properties in foreclosure, but the banks didn’t seem very interested in selling them. My favorite part of the forum is when the banking executive told me why. Banks had such an excess of properties in foreclosure on their books, that to sell them at their market value (about 40% less than book value), and write-off the losses would have rendered the financial institutions insolvent. So they just didn’t sell them. During the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021, the unemployment rate from the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed both the unemployment rate at 6.2 percent, and the number of unemployed persons at 10 million. However, loan delinquencies went down — even with the high unemployment rate and the strong historical association between the unemployment rate and loan defaults. A 2021 article in Fortune Magazine, based on a study by business schools of Columbia University, Northwestern University, Stanford University, and the University of Southern California, found that in the Great Recession, mortgage delinquencies jumped from 2% to 8%. But in the pandemic’s first seven months they fell from 3% to 1.8%. “This is especially striking,” the researchers note, “given an unprecedented increase in the unemployment rate that reached almost 15% in the second quarter of 2020.” And, they found that the explanation went beyond just stimulus checks. Fast forward to 2023. TransUnion’s (NYSE: TRU) 2023 Consumer Credit Forecast projects delinquency rates for credit card and personal loans to rise to levels not seen since 2010. Card delinquency, on the rise in 2022, is projected to increase to 2.6% through the end of 2023, which would represent a 20.3% increase year-over-year. This is attributed to persistent inflation and high interest rates. Bloomberg predicts that credit-card rates are poised to hit a four-decade high this year. Bankrate predicts an average interest rate of 20.5% in 2023. And some retail-brand credit cards have already surpassed 30%. Just to give you an ideas, pre-pandemic credit card interest rates were around 17%, but fell below 16% when the pandemic hit. Which brings me to my point: the reason why credit card interest rates when down during the pandemic was to help people and help banks keep delinquencies low. Banks and credit card companies now need to heed what they did during the pandemic to avoid a repeat of the Great Recession. Here are six strategies financial institutions, including credit unions, deployed during the pandemic that should stay in effect now: 1. Utilize forbearance. Instead of cracking down on delinquent borrowers, offer forbearance. That way, borrowers can delay loan payments without you declaring the borrower delinquent. It also improves your borrower relations by not diminishing the borrower’s credit rating. You will still take a hit on revenue, but only temporarily, and you don’t have to worry about a portfolio of foreclosed assets to liquidate. 2. Offer a variety of payment options. You can decrease your delinquencies by offering various payment options to your borrowers. Anyone struggling financially can pay principal-only, interest-only, or a combined payment. You could also reduce the minimum payments if possible. Be creative. 3. Encourage recurring payments. Offering recurring payments makes bill payments easier and more timely. This is especially helpful for busy borrowers or those who travel. 4. Encourage paperless adoption. Studies show that those borrowers who receive electronic bills tend to be more satisfied and reliable borrowers. According to an article from My Billing Tree: “By encouraging paperless adoption, you are in turn developing a more satisfied customer base. These customers, in many cases, are then more likely to be receptive to other types of account management features, including enrollment in recurring payments.” 5. Accept payments regardless of method or channel. In addition to different payment amount and delivery options, you can also provide different payment methods and channels. Borrowers can call and pay by phone, or even text to pay. 6. Improved information from technology. With online and mobile banking, borrowers can check their balances in real-time. Upcoming loan due date reminders can be emailed or texted to them. Pending payments can be posted to avoid overdrafts. We cannot overestimate the importance of technology in avoiding delinquencies and making borrowers happier. Loan delinquency rates could improve more, due to robust employment numbers. The important thing to remember is that most borrowers want to pay their bills and pay them on time. With these proven methods, credit card companies and banks can do their part to help with the economic challenges their members have. By smartly learning from the past, financial institutions can improve their delinquencies, borrower satisfaction, and bottom line. A previous version of this article was published on CheckAlt. … even if you are making a profit. Working Capital is the lifeblood for most businesses. It can make the difference between surviving and growing or going bankrupt. Working capital is all about planning, negotiating and timing. Oftentimes, owners learn this the hard way. After leaving the investment banking world, my then husband and I started our own business. According to family folklore, his father’s plastic manufacturing business had patented the original Hula Hoop which was featured on The Art Linkletter Show and immediately became a worldwide fad, its sales estimated to be over 100 million hoops in two years. After those two years, his family went back to their regular plastic extrusion business for OEM customers like automotive companies and the like. Whamo registered the name and continued selling them, albeit in much lower numbers. At the 50th anniversary of the launch of the original, a cousin asked us to make hoops for their chain of American Greetings stores which numbered about 50 or so. We updated the colors to fluorescent shades and they looked fantastic. We named the hoop the Maui Hoop and called our company Maui Toys. We invented three more products, went to our first trade show, the International Toy Fair in New York City, and our toy company was off and running. Maui Toys was soon selling to large retailers such as Toys “R” Us, Walmart, Target, Kmart, Children’s Palace, and a slew of other smaller chains and independent toy stores. It was great fun, but we were facing a looming working capital problem. We were self funded and it was one thing to make a few thousand hoops for one smallish store chain, and it was another to make hundreds of thousands of hoops for huge chains such as Walmart. Working CapitalBefore I get to our survival strategy, let me explain what working capital is for those who don’t know. It is the money a business needs to cover the gap between paying bills for its manufacturing or purchases of its products and collecting money from the sales of those products. This can pose a problem. Why? Let’s use the example of making hoops. You order your hoops from a plastic manufacturer, in this case a plastic extrusion company. Think of extrusion as the famous Play-Doh machine where you put a ball of doh in the little mechanism, a shape at the end (called a die) and you push the Play-Doh through. It comes out as a long tube of doh in whatever shape you have chosen. Obviously for the hoop a circle die was chosen. Your extruder makes your products and gives you a 30-day invoice which means you have to pay them in 30 days for the plastic tubes. Let’s assume that bill is $250,000. Then you have to pay factory workers for assembling the hoops in a circle with a connection plug, put a label on it, and pack it into a box for shipping and displaying at the store. Your toy company has to pay the factory workers their salary in addition to payroll taxes bi-weekly. You also have to buy a label from a printing company. It’s a small expense but has to be paid up front until you can establish a credit relationship with them to get 30-day terms. Let’s say all of that costs roughly $14,000. Most of it has to be paid in 30 days or less. You ship your boxes of hoops to your biggest customer and invoice them. They have 60 days to pay you and you find that they often stretch that out to 90 days and sometimes even 120 days. According to the following, hypothetical and very simplified cash flow/working capital projection, by month 4 you need almost $278,000! That’s assuming your customer pays you in 90 days and you have to pay your plastic manufacturer in 30 days. Timing You’ve had to spend about $280,000. Your invoice to your customer is $500,000. There is a lag effect where you have to come up with almost $280,000 dollars to pay your suppliers and you won’t receive your $500,000 from your customer for another 90 days. That’s a working capital problem. By the way, you’ve just made a huge profit. But, how do you bridge the 60, 90 or 120 gap between paying your bills and receiving your money? Hard to put $280,000 on a credit card. Maui Toys didn’t have that kind of money. Nowadays, founders might raise money as seed capital from an investor and give away a percentage of their company’s stock. We came up with another solution. The number one reason why we were able to survive and grow our business: We asked our plastic manufacturer to accept 120 days for our company to pay their invoice. They said, yes. They gave us 120 days to pay our bills. Technically, they gave us 30 days and we didn’t pay for 120 days. And they didn’t sue us. Or shut us off from future purchases. Labor and other costs still had to be paid for, but they were a relatively small percentage of the overall cost so we were able to cover that ourselves. We were lucky because we didn’t have to give away ownership to get started. In the startup world that’s called bootstrapping it. Increase Your Working Capital

To summarize, these are the steps you can take to increase your working capital.

And remember, the truth is always in the numbers. Originally published at https://www.datadriveninvestor.com on August 10, 2022. What is McDonald’s business? Some might say, the fast food business, or more broadly, the restaurant business. But what many people don’t realize is that McDonald’s is really in the real estate business.

Their real estate holdings include land and prime building locations around the world where their Franchisees build restaurants and pay them rent, month-in and month-out. That’s where McDonald’s makes most of their money, more money than selling burgers. I remember watching, “The Founder,” a 2016 film about McDonald’s history. “You don’t build an empire off a 1.4% cut of a 15 cent hamburger, you build it by owning the land on which that burger is cooked.” Decent flick by the way if you haven’t seen it. Southwest Airlines flies people around, but they are also adept at buying and selling oil futures. They do it really, really well. What started out as a way to hedge against fluctuations in fuel prices back in 2007, ended up being a major profit center for them. And while other airlines were losing money when oil prices skyrocketed, Southwest made money. Another good example is Amazon. According to a February 2022 article in Investopedia, while the majority of Amazon’s revenues comes from online and offline retail sales, the majority of its operating income is from AWS or Amazon Web Services. It is the world’s most comprehensive and broadly adopted cloud platform. Many car companies earn very thin margins selling cars but make up the difference both through financing those cars and inside their service departments. So are they in the car selling or the car servicing/repair business? Are they in the financing business? Of course it depends on the particular car company. Which begs the question, do you know what business you are really in? The best way to find out what business you’re in is to give the different departments (or product lines) inside your company their own financial statements. That amounts to extra accounting work, but not that much compared to the benefits that knowledge will give you. Break down each department’s sales, cost of goods sold, and expenses specific to them. You can apportion the time expense of employees who manage and work for different departments. You can also apportion rent, utilities, equipment, and so on. Then analyze and compare the financials. Which department is making the highest profit margin? Which one is generating the most cash flow? Chances are, that’s your core business. Why is this important? This is important because once you figure out what your real business is, you have to protect that and feed it. Spend extra money to make sure it is well staffed and well stocked. Veer marketing and advertising dollars in that direction. Give it the most attention. Doing this will protect your overall business. When I was a partner in the apparel business, XLARGE Clothing, we had half a dozen retail stores in addition to selling to major retail chains, bougie boutiques, and international licensees. What business were we in? XLARGE designed an entire collection four times a year: spring, summer, fall/back-to-school and holiday. The collection included everything from graphic tees and sweatshirts to jeans and work pants to accessories (belts, backpacks, etc.), to button down shirts to outerwear and even shoes. We did a lot of collaborations too with artists and other designer brands like, Vans and The Hundreds. Our retail stores were in San Francisco, Orange County, SOHO, and Los Feliz. Licensed XLARGE stores were in London, Germany, Taiwan, China, Hong Kong, Australia, Korea and Japan. The licensed stores had to buy all their clothes from us. We had a girl’s line, X-Girl and later, x’e. And our kid’s line was called, X-Little. And we sold to retailers such as Urban Outfitters, Bloomingdales, Journeys, Hot Topic, Federated Department Stores, PacSun, and many other cool stores like, Colette in Paris. It was really the best job in the whole wide world. The Beastie Boys were partners and we had a lot of great parties and store openings. Many wonderful artists worked for us and with us. My duties included traveling to Tokyo and New York City. It was hard work but great fun. Work hard. Play hard. Where do you think we made the most money? Well, it certainly wasn’t our retail stores. Retail is a difficult place to make money even with the vertical integration and resultant hefty gross profit margins that affords. We didn’t make that much money for most of our clothing collection either. Our volume wasn’t quite high enough to get the pricing we needed to be competitive. Most of our licensees had one or a handful of stores so they didn’t really buy enough from us to be a contender for our largest generator of profits. Diversification is good and we had many different sales channels that helped us achieve that; we didn’t want to throw out the baby with the bath water so we carefully evaluated all our different departments. Our true business, our real business, the thing that made us the most money was two things: graphic t-shirts and sweatshirts, and our Japanese licensees because they had eighteen stores. Nothing else came even close. Since I was the CFO, I closed most of our stores except SOHO and Los Feliz and wrote off those losses as advertising expenses, because that’s what they were. We also quit selling to most of our wholesale accounts because they weren’t worth the expense of a sales force and the merchandise returns were shameful. There were more things we shuffled around and refocused on. We hired additional, talented graphic designers for more tees and sweatshirts. We transferred the manufacturing of the collection to our different licensees and they had to pay us simply a licensing royalty instead of buying the entire collection. They still had to buy tees and sweats from us. All of these moves made our company immensely more attractive to the point where we were able to sell it to our Japanese licensee for a spectacular return. XLARGE is still around today and still a super cool, niche, streetwear brand. All of this analysis taught us we were in the business of making t-shirts and sweatshirts and selling them to Japan. The role of the customer. Sometimes a less profitable part of your business feeds customers to the more profitable part of your business. It’s similar to a loss leader in a grocery store. Using the car dealer example above, perhaps they make most of their profits in car servicing, but without selling customers the cars in the first place, they wouldn’t have a servicing business. That needs to be taken into account as well and can be established by doing a customer analysis. Think of it like computer analytics which tally where your customers originate. Are they being referred from a blog? Your website? Google searches? Social media posts? You should be able to track that. If most of your customers are coming from outside your website, then don’t invest too much time and money on your website. Or if the bulk of your business is coming from social media, then don’t spend money on Google ads. The important thing is to know your business. Know where you make the most money, what has the most potential and where your customers originate. Then spend more time nurturing those things. And remember, the truth is always in the numbers. Originally published at https://www.datadriveninvestor.com on May 12, 2022.  Road Trip with Raj@roadtripwithraj Road Trip with Raj@roadtripwithraj In the next couple weeks, a friend’s business is going to shut down and close its doors. Their customers canceled all outstanding orders. The only channel left for them is online sales, where their gross profit margin is 4%. Yes, gross profit margin, not net profit margin. In the meantime, their overhead costs are continuing unabated, eating all their available cash like a Pac-Man at warp speed. How can this company be saved? I reflect on that now ghostly column started in 1952 in Ladies’ Home Journal, “Can This Marriage Be Saved”? A long time ago when I was a young girl, I would read my mom’s copy each month. Marveling at how poorly husbands and wives treated each other I thought, quite decidedly, that I would never ever get married. But if I did, I would never let my spouse treat me so shabbily! Even today, if you Google, ‘can this marriage be saved’, there are over eight million results ranging from deep psychological probing to reading the ‘signs’ to taking pop quizzes, ostensibly because you cannot read the signs. If you Google, ‘can this company be saved’, there are precious few results. Most are about saving money, a component to be sure, but not really about saving the entire company. The thing is, I’m not really interested in the question, can this company be saved? I’m more interested in how this company can be saved. I’ve had more than a dozen of my former clients and friends call me in the last couple of weeks. They are understandably concerned about whether or not their companies are going to survive. This is something on everyone’s mind in the age of Covid-19 and the lockdown of America and the rest of the world. It’s everyone from CEOs and investors to bookkeepers and shipping clerks. I suppose the good news is that we’re all in this together and to some extent, we can assuage ourselves with the camaraderie of the situation. But if you own or run a company, the most vital question is, can it be saved? And how can it be saved? Doug Yakola has been running recovery programs for over twenty years from the prestigious management consulting firm McKinsey & Company. In a post about leading a company out of crisis, he explains that even good managers are often working under a set of paradigms that no longer apply while letting the power of inertia carry them along. Nothing like a worldwide shutdown to shift your paradigm. The good news is, we all know that the rules have changed. So here we are, now what do we do? Leaders need to make tough decisions and act quickly. To navigate these challenging times, executive leaders need to make tough decisions, act quickly and remember that the number one goal is to save the company while minimizing collateral damage to your community and workers/employees. Every business is different to be sure, but these classic turnaround strategies will apply to almost all of them. I’ve outlined some steps to get you started, with additional detail below. Even if you don’t own a company, you can employ some of these strategies for your household.

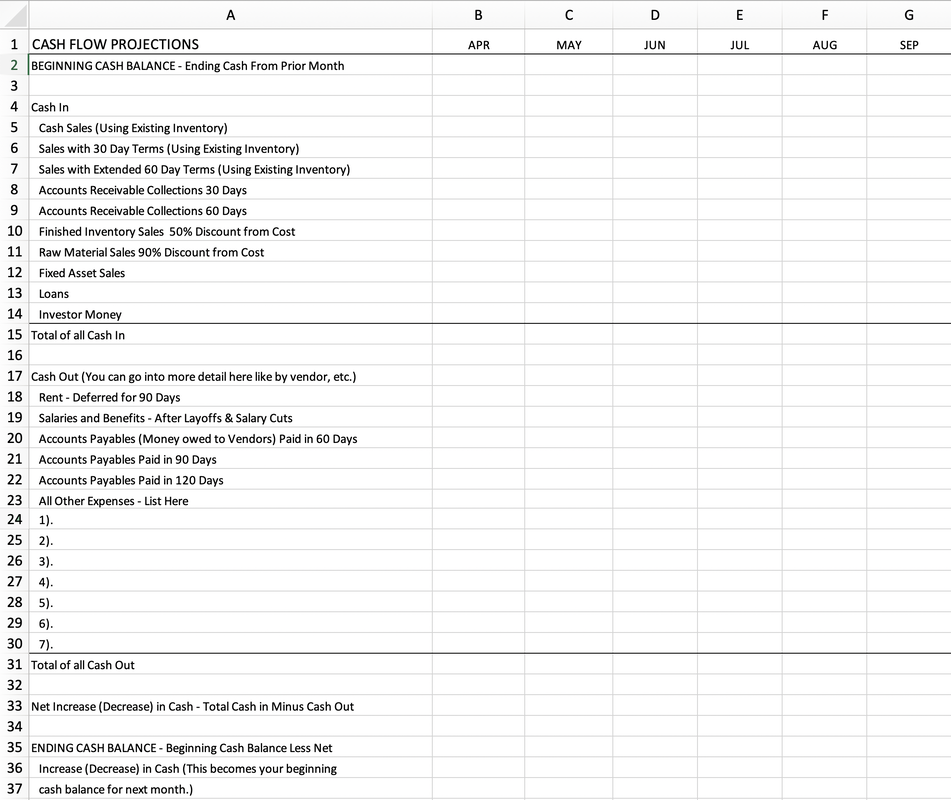

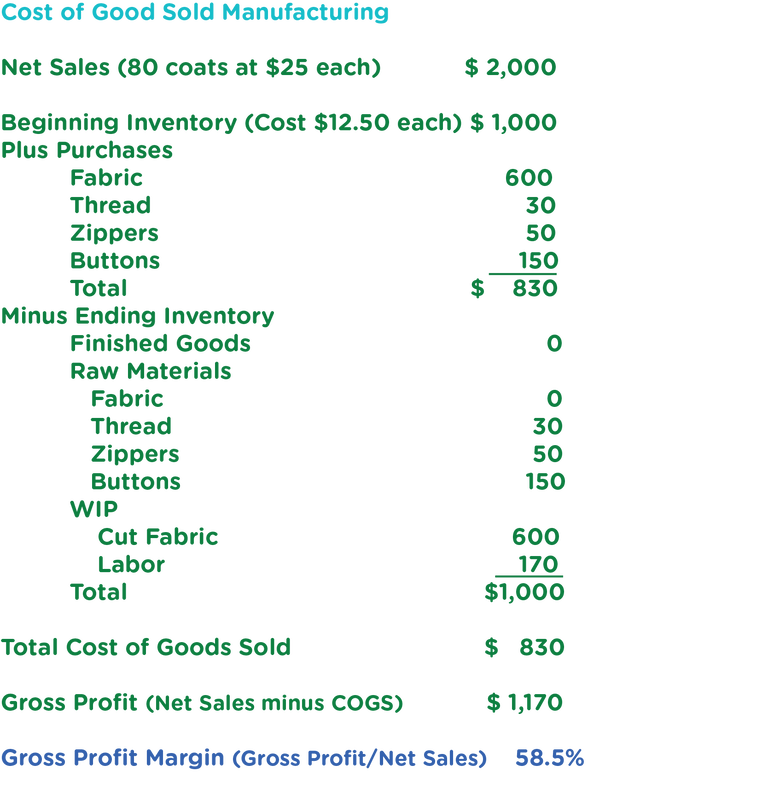

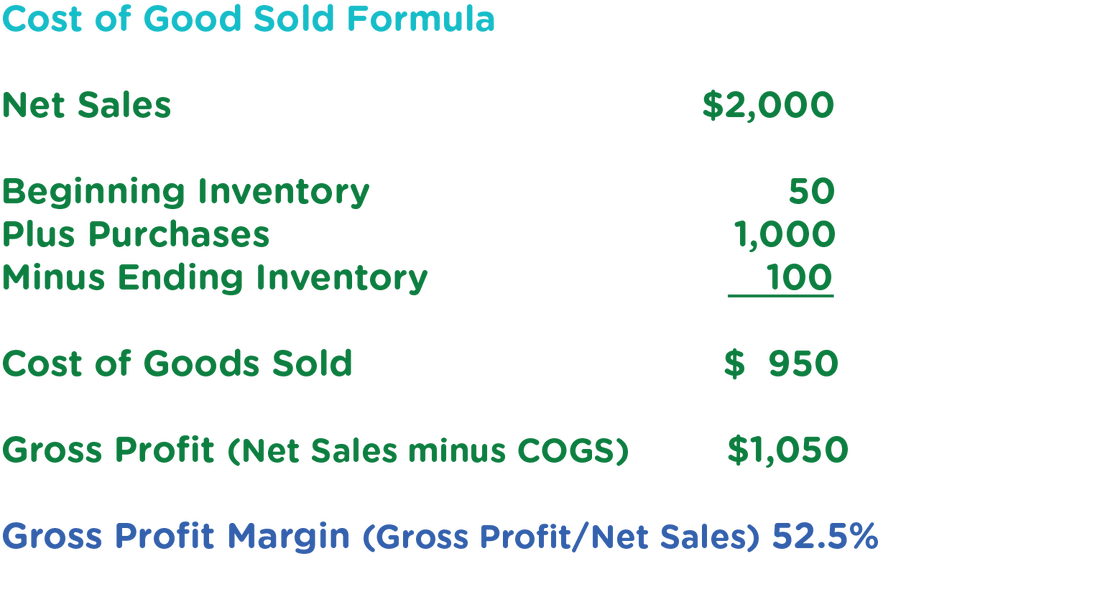

Don’t freeze. I know you may feel paralyzed right now, but the most important thing is to be in action — not motion, but action. What is the difference? James Clear explains it perfectly in his book, “Atomic Habits.” Motion is a planning process, a thinking, a mulling it over if you will. Action is actually doing it. Let’s say you want to write an article. Motion is sitting around thinking about it. Turning over the story in your mind’s eye. Maybe even doing research or making notes. But at a certain point, you have to sit down and write. That’s action. If you want to survive, you must be in action like Nike’s great slogan, “Just Do It”. Estimate how long this downturn will last. You may be wrong, but you may be right or only slightly wrong. Collect all the information you can and then take your best shot at estimating. That’s what projections are anyway — your most educated guess as to what is going to happen. If you at least have a set of assumptions and the resulting actions based on those assumptions, it is easier to make adjustments than it is to start from scratch or to have no plan whatsoever. Collect and hoard cash. See how much cash you have. This includes checking and savings accounts, bank lines of credit, credit cards, cash on hand, and investor commitments. (Confirm those commitments.) Tally up your accounts or loans receivable (money your customers or others owe your company) if you have any. Make an aggressive effort to collect all of that as soon as possible, even offering a discount if you can get a large portion now. If you have open lines of credit, borrow the maximum on them and tuck it away. Remember, in times of difficulty, Cash is King. Ironically, I recently wrote about that. You can find it here. As an example, last week when a large tenant of mine asked for a 50% discount on his monthly rent, I offered, if he paid me in full for April, I’ll waive the following two months rent. That would result in a 66% discount for him. But I’m getting the cash up front. Who knows? He may go out of business next month. His company perhaps cannot be saved. Salvage outstanding orders. How many orders can you save using existing inventory? Don’t make any new inventory unless you have an order that will use all of it and at a good price. Call all your customers. Maybe give them extra terms. Let them know that if they take your goods in today, you will give them sixty or even ninety days to pay for them. If they buy now, you’ll give them a discount. Better to get something for your inventory than to have it sitting in the warehouse. Project cash coming in. On a spreadsheet or piece of paper, write out the name of each month until you assume this will end. If you think it will be over in six months, then make the heading on top for the next six months — APR, MAY, JUN, JUL, AUG, SEPT, OCT. Write down your best estimate (based on the data collection you just did by questioning your customers), of your cash in — not just your sales — but when you will collect the money. Also include in cash, the amount of receivables you think you will collect under the month that you think you will collect them. This is the first part of a cash flow statement — when the cash is coming in. And be super honest and realistic with yourself. I’ve constructed a rudimentary Cash Flow Projection you can use as a template below. Project cash going out. If you are to make no changes, what are your expenses in the month the cash is going out? Look at keeping all your staff, paying your rent in full, payroll taxes, utilities, commissions, shipping, postage, etc. Subtract your monthly expenses from your estimated revenue. See what your shortfall is each month. If you have a shortfall of $10,000 every month and you have access to $30,000 in cash, then you’ve got three months of runway. That’s your worst case scenario. Now for the important part — let’s improve upon that. What are the two main categories of improvement? Increase or speed up cash in. Or decrease or slow cash out. Explore alternative sources for cash. As an example, find out how much money you can get from the SBA (Small Business Administration). The SBA is guaranteeing loans for companies and if you can keep your employees, it turns into a grant (which means you don’t have to pay it back). Make that adjustment of cash in the column of whatever month you can safely assume you’ll receive it. Can you liquidate any of your inventory? If you don’t have enough sales to use up your existing inventory (goods on hand or in your warehouse), then see if you can sell them for a “closeout” price — which usually means for ten cents to fifty cents on the dollar. If you are making a gadget that costs you $1.00, you will sell it for 50 cents. There are closeout companies in your industry. I guarantee it. Google it. Ask friendly competitors.They are out there. You’ll book a loss, but we’re concerned with cash here, not losses. Cut or slow down cash out. If you can slow down your payables (people you owe money to), or negotiate longer terms, or a lesser interest rate to your bank if you owe money, or deferred rent, or reduced shipping costs or wherever you can save money — do it and don’t wait. Like my friend, if all your sales are now online, then look at your server costs (believe it or not there can be a huge difference), drill down on your shipping costs, (pit Fedex against UPS or USPS), that’s a simple one and can be easily delegated. How can you save money on packaging? Boxes? Labels? If it’s a food company, it may be less expensive to overnight your items than pay for dry ice. Just be creative. Think outside the shipping box. Weed out lower profit margin products or services. Look at your product mix. You should know how much gross profit you are making on each product/product line. Gross profit is the sales price of a product or service less what it costs to produce or provide it. If it’s less than 30% of sales, consider dropping it. As an example, if your main product is pizza, but you supplement that by salads and wings and you make a 30% gross profit margin on wings, and only 20% on salads, then consider dropping salads from your line. It pains me to say this because I’m a vegetarian, but I’m not really your customer, am I? Trust me, there are still plenty of people that buy pizzas. If you don’t know your profit margins for each of your products, hire a good bookkeeper. I can recommend one. Or ask your accountant to help you (for a deferred payment or perhaps even barter). Free pizzas for life! Pun intended. Yes, don’t lose your sense of humor, not now as you may need some levity to balance the balance sheet of stress. Employees you should keep. If you are a consumer products company that sells to other retail stores, then your salespeople are gold. If you sell online, then your marketing people are gold. Look at where your business is right now, and lay off employees that you don’t directly need for what you’re doing right now. When things get back to somewhat normal, then you can re-adjust your employee mix. A word: please try to make this your last possible option. We’re all in this together and laying off employees will have ripple effects. If you can, perhaps try to pay everyone at half salary. After you’ve examined all of this — and this is not a gut instinct situation, this is an information gathering and numbers crunching situation, make a plan and meet with your stakeholders. They may include, board of directors, investors, and partners. Come armed with your six month projections and assumptions. Be forthcoming. If you have completely honest and well-thought out information and research backing up a Master Plan, they will be much more likely to support you. Schedule a meeting with your bank. If you need them to lend you more money, and show them your realistic and conservative Master Plan, you have a better shot. If you can’t make your payments on a timely basis, then tell them. As a former banker I can tell you one important fact: bank’s don’t like surprises. Yes, it’s true. Your bank or investor or factor will be much more likely to support you if you meet with them, clutching your Master Plan in hand with an up-to-the-moment financial picture. This is not an online dating profile with a ten-year old photo. They don’t want you to bullshit them; they not only want you to succeed, they need you to succeed. They don’t want to be left in the dark either. Give them the honest information up front and keep them updated with excruciating frequency. Weekly at minimum, daily if necessary. You would rather that they’re sick of you — “OMG, it’s her again” — than for them to be wondering, “what ever happened to her? I haven’t heard from her in months!” It’s probably not comfortable, but it’s always better. I have three final words for you: plan, plan plan. You must start and finish with a plan. Be conservative (provide a cushion). Change it as you go. Communicate it to everyone relevant. And remember, this too shall pass. Here is that Cash Flow Template I mentioned: Many companies don’t really understand what a cost of goods sold is and don’t calculate it correctly. I’m going to tell you why that’s dangerous. I get endless writing fodder from my clients. I am currently working with a company that is acquiring another company. My partner and I were retained to calculate a valuation and propose an appropriate deal structure. Easy peasy. Right? Wrong. The target company is a manufacturing company and their cost of goods sold (COGS) was wrong in six ways from Sunday leading to an inaccurate gross profit margins. It is difficult to value a company without a solid COGS and gross profit number. Further, it is difficult to make decisions about your company if you don’t know what your COGS is.  COGS Formula Let’s start with the formula for COGS: beginning inventory plus purchases minus ending inventory. That’s it and it is logical. It’s what you started with (beginning Inventory) plus what you purchased to add to that (purchases) less what you have left over (ending inventory). Why subtract ending inventory? Logically, because it is the Cost of Goods Sold. If you don’t sell it, subtract it out and it will be your ending inventory for this period and your beginning inventory for the next period. Yes, it is calculated for a particular time period. For small companies that is usually monthly, quarterly and then at year end. The idea is that you want to find out exactly what it has cost you to make or buy the products you sell for that time period. So it is only that. Not sales commissions or whatever it cost you to sell them. Not what it cost you to store everything in your parent’s garage. Not what it cost you to make samples or go to trade shows or advertise. None of that. Just, what it costs to make your products. The only exception to this rule is if you are doing your own actual manufacturing. Then you can include factory overhead expense into COGS for the time period in question. Inventory Valuation To drill down to the component parts, inventory is the entire cost of your products to get it to your warehouse and only that cost. Not what you’re going to charge your customers or retailers. That’s your wholesale price (if your selling to stores) or your customer price (if you’re selling directly to customers). And inventory should always be the lower of cost or market value. So if it cost you $10 to make a widget and you make 100 widgets, then the total value of your inventory is $1,000. If the market value (what you are going to sell it for) is $5,000, your inventory number is still $1,000. ( Lower of cost or market.) But if the market crashes for your widgets and you can only sell them for $500, then your inventory should be listed at its market value of $500. ( Lower of cost or market.) A note about the gray area of inventory valuation It is very easy to manipulate your inventory to make more money or lose more money. It is the easiest way to affect profits and losses in business. Why would one want to do that? If you have bank loans that require you to make a certain amount of profit, you would want to value your inventory as high as you can. If you have a privately held company and your goal is to pay the least amount of taxes, you would want to write-off inventory that has aged, as much as reasonably possibly. I am not suggesting you do that because you need to show an accurate inventory valuation and you don’t want to get in trouble with banks or the IRS, however, it is something that is often done. Don’t do it. And by the way, it will eventually catch up to you down the road. Purchases Purchases should include the total that you paid for your widgets, $1,000 in my example, and how much it cost you to ship it into your warehouse or parent’s garage (part of your cost and called “freight-in”). If you are importing, you should also add in customs and duties as a part of the freight-in cost. Manufacturing If you are manufacturing it gets a bit more complicated. In that case you have to add together purchases of all the raw materials required to make your widgets and still include freight-in that will hopefully be less than shipping it from a foreign country if you’re using parts made nearby. In this case your inventory number should also include raw materials and work-in-process (or progress), or WIP.

Let’s say you are manufacturing coats. You have an order for 80 coats at $25 each. Luckily you start out with 80 coats that cost you $12.50 to make. But you want to make more inventory in case you receive more orders. You buy the fabric locally and ship it to your factory. You also purchase thread, buttons, zippers and tags (raw materials). At the end of your reporting period, 12/31/22 (called a fiscal year), you had personal problems and were only able to cut the coats out of the fabric. Since you haven’t sewn and finished them, they are considered WIP. Your purchases would be all the raw materials that your company purchased along with the cost to ship them to you. Your ending inventory number would include any finished inventory (that you don’t have in this example), all of the raw materials that you haven’t used yet and WIP (which now includes all your fabric because you cut it). Your only sales (since you haven’t finished making your coats), were from beginning inventory or the coats you made from last period. Why your COGS is so very important Now that we know how to calculate an accurate COGS, let’s discuss why it is so very important. You need an accurate COGS to calculate your gross profit. You must have an accurate gross profit to make important decisions about your company, to price your goods and to ascertain if you’re making any mistakes so you can fix them. As an example, If your gross profit is too high, you may be charging too much for your products and by lowering your prices, you could increase your sales enough to more than compensate for your lower prices. If your gross profit is too low, maybe you are not charging enough and could raise your prices, sell the same amount and make more money. A major problem with a COGS that is too high, is that you purchased too much inventory. That eats into your COGS percentage as well as your cash flow. It can also be that you paid more than you estimated for your products or raw materials. Sometimes, freight-in costs can be increased at the last minute (a problem with many companies in the last year). I’ve even seen companies that forgot to add in an important raw material when pricing their product. Try to add a cushion into your pricing too account for problems that crop up. For more information about pricing read my November 2019 article, “The Art of Pricing.” Cash flow problems with inventory At a minimum, you must make enough gross profit to pay your overhead expenses such as design, marketing, sales, rent and salaries. If you purchase too many products, much more than you have orders for or more than you can sell, that is going tie up your money in inventory and you may not have enough cash flow to operate your business. I’ve seen many small companies go under because the cash they need to run their company is sitting in their warehouse in the form of inventory that can’t be sold. Often this happens because there are certain minimum order quantities they must purchase. And people think their products are great which they may be, but they are overconfident that they can sell them. For more information on cash flow, read my March 2020 article, “Why Cash is King and How to Get More of It.” In closing, keep a handle on what it takes to manufacture or purchase your products. It will be the foundation of your decision-making and most importantly, the source of your cash. Research suggests that up to 70% of partnerships fail to deliver their intended outcomes. That’s an incredibly high number and one that borders on emergency status.

I’m reading “Klara and the Sun,” by Kazuo Ishiguro. It’s a wonderful book about an A.F. (artificial friend) named Klara. Klara is delightful, curious and observant — a good A.F. And the story, told in a first person narrative with Klara being the narrator, adds an element of fascination. I find myself considering, wow, this is how a robot might “think”. Klara’s “life”, so far (I’m about halfway through), is relatively simplistic as you can imagine a robot’s life would be. She knows her place, is well-mannered, puts her real-life friend, Josie, first, and isn’t emotional about any of it. It got me to thinking about business, specifically partnership problems in business that often arise because partners don’t respect each other or are simply too emotional about their issues. I have one consulting client right now going through partnership challenges. They’re looking to sell their company to ostensibly buy out a couple of their partners. I also recently spoke to a potential client who is considering drastic steps with her company due to problems with one of her partners. And there’s more! Partnership problems seem to be coming to me more frequently of late. Sometimes I feel like I should have a degree in psychology instead of economics. It brings to mind my own relationship with my partner in my last company. We worked together for twenty four years, sold our manufacturing company after my twelfth year, bought commercial property and multi-family housing units and kept going together for another twelve years investing in real estate. We did very well. In all our years working together I can’t remember one significant fight or argument. After much thought, I put together a list as to how I think we accomplished this.

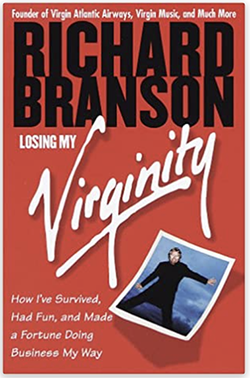

None of these things is revolutionary. Everyone can do them. Treat your partner like you would like to be treated. Even minority partners. If they want more information, give it to them. If they want annual meeting notes, write them. Have mutual respect and keep your emotions in check. Remember, it’s not personal. It’s business. In short, be more like Klara. Business is stressful because things are always going wrong. As a CEO you might wonder, when is this going to end? When will it get easier? What level of sales or profits do I need to attain? At what point will my business be strong enough and healthy enough that I’m not constantly worried it will somehow crash and burn? I was a founding member of a group of entrepreneurs called, The Startup Founders. We were all in various stages of starting and growing businesses. As we grappled with the day-to-day challenges that a startup must shoulder and solve, the group gave us a safe place to process “issues.” They could be anything from problems with a partner or in my case, a substitute for not having a partner. There were also the questions relating to raising money, formulating a business model, or pivoting when that model wasn’t working. It was a case of helpful collective intelligence. One day I was talking on the phone to a fellow member who came up with a brilliant idea relating to photo storage. She was complaining how difficult the process was, and how she was so tired of fighting through all the problems that kept appearing at her doorstep, like that trick-or-treating kid who kept coming back for more candy. At one point she cried out, “When is this going to get easier!?” Before I answered her, I thought of a great book I had read that perfectly answered this question. It’s actually one of my top ten business books, “Losing My Virginity,” by Richard Branson, and I highly recommend you read it. The subtitle is, “How I’ve Survived, Had Fun, and Made a Fortune Doing Business My Way.” A little wordy to be sure, but it well describes the contents and pearls of wisdom contained therein.  Reading about Branson’s trials and travails when he started Virgin Airways is when I had my epiphany: It’s always hard and it never gets easier until you sell the company.True story. Even when Branson was running an actual airline and he was a billionaire on paper, he was still fighting with British Airways almost every single day in addition to all kinds of problems like labor and mechanical issues and scheduling and cash flow and raising money and paying off debt and … you get the point. As Roseanne Roseannadanna, played so brilliantly by the late Gilda Radner used to say, “It just goes to show you. It’s always something. If it’s not one thing, it’s another.” And that was my epiphany. It’s always hard and it never gets easier until you sell the company. If it is hard for Richard Branson, it sure as heck isn’t going to be any easier for me, for us. I told my friend that. I told her that it’s never going to be easier until she sells her company and just knowing that, going into it, makes it easier. Right? If you know this, you can roll with the punches, you can not be disappointed when your expectations are not being met, because basically, you cannot have any expectations. You just take it one step, one day at a time. And then you’ll be fine! Trust me! I’ve built three companies from the ground up.  It also brings to mind another one of my top ten business books, “How to Stop Worrying and Start Living,” by Dale Carnegie. It is chock full of helpful methods and processes to actually cure your stress and worry problems. Chapter 3 in his book is called, “What Worry May Do to You.” In that chapter he quotes Dr. Alexis Carrel, Nobel prize winner in medicine: “Businessmen (okay, it was written in the 40s) who do not know how to fight worry die young.” Then Dale Carnegie gives you multiple ways and means that you can deal with your stress and worries. I’ve read this book dozens of times. In an earlier Medium Article I talk about one of his methods that has worked for me every time, “Before You Freak Out, Ask Yourself These Four Questions.” In the end, my friend didn’t move forward with her business. The biggest issue was that Google happened to come out with a product very similar to hers and she felt that it didn’t make sense to continue. Understandable. At least she knew early before she pumped more money into her venture. I’ve shared my epiphany with many others since that time, with the hopes that it would help them manage their expectations. I believe that it has helped. I know that it has helped me. P.S. Congrats to Sara Blakely for selling her Spanx business to Blackstone yesterday. She can now take a well-deserved, deep relaxing moment. I’m sure she’ll be back at it soon. and how to get more of it.

In the last two weeks, my stock portfolio dropped significantly in value, and I don’t care. Why? Most of my stocks are dividend paying and thus far at least, the dividends haven’t been cut. What matters is the cash they’re generating which I depend on for a part of my income. That hasn’t changed. Also, I’m quite a ways from retirement, so I can sit tight and wait for the next upswing. The cash generated through dividends is more important than the value of the underlying stock. Cash is king. You may have heard that old saying. Basically it means that cash is more important than the value of assets or even your profits. And most of the time it is. Here’s another example. I bought a house with a 30-year fixed mortgage. My mortgage payments were not going to increase. I worked my monthly payment into my budget, and I knew, based on my income, that it was affordable as long as my income didn’t decrease — not likely. Then, the Great Recession of ’08 happened. My house dropped significantly in value and I didn’t care. Why? My monthly payment remained the same, my income remained the same, and I wasn’t going to sell my home anytime soon if ever. The value of my house didn’t matter and I knew it would go up again eventually because it is in a great neighborhood. And it did. Cash for Your Business What is a cash flow statement? It’s cash in less cash out. If your business is cash flow positive every month (more money is coming in than going out), you’ll be okay. What is an income statement? It is revenue or sales, less expenses. The result is your monthly profit or loss. You can operate at a loss for a period of time, and as long as you are cash flow positive, you can still be okay. Here are some suggestions for how to manage your cash flow in a business:

Cash for Your Personal Life As far as your personal life, there are several ways you can make sure you have adequate cash on hand for emergencies. Here are some tips:

The bottom line is that you want to always have cash on hand one way or the other for both yourself and your business. Cash is king. |

Stories and snippets of wisdom from Cynthia Wylie and Dennis Kamoen. Your comments are appreciated.

Archives

June 2024

Categories |